Thursday, December 01, 2005

Off Season Digest # 4: Should I Be Happy?

That being said, 2006 could be a good year to go to Shea.

Monday, November 21, 2005

Off Season Digest # 3: Goodbye Mr. Cameron

So just who is this opening up room for on the payrool? Carlos Delgado? Manny? Damn, I love the hot stove.

Wednesday, November 09, 2005

Off Season Digest # 2: Can You Take Howie With You?

Alas, that isn't likely to happen. But what this move does mean (and I hope I'm not cursing Mets fans by saying this) but it looks like Fran Healy is FINALLY OUT. YEAHHHHHHHHHHHHH! Every single report about the SportsNet NY analyst job has focused on Keith Hernandez or Al Leiter, and either of those I could handle. One would imagine that the okay team of Dave O'Brien and Tom Seaver will stay on the Ch. 11 side of things.

Once again, congratulations Gary, and I look forward to listening to you for many years to come.

UPDATE: It looks like Cohen will be doing all 162 games for the team, which I guess would include Ch. 11 games, according to NYSportsDay.com. Plus other folks chime in, like Faith and Fear and MetsBlog.

Tuesday, November 01, 2005

Off Season Digest # 1: Where Will You Go Theo?

In Mets news, I'll never have to spell Doug Mientkiewicz again. Or worry about Braden Looper. Take a guess at which one I'm going to miss more...

Thursday, October 27, 2005

Is It February Yet?

So the White Sox are the latest team to break a lengthy curse--are the Cubs due in 2006? (Not bloody likely.) And now our nights are filled with, well, nothing but Simpsons reruns, and once a week, Lost. This is the time of year that always depresses me--no box scores, no analysis in the morning paper, nothing. And don't get me started about people who claim that the NFL is the best sport in the land. Ugh.

The Zisk site will probably be in hibernation until pitchers and catchers report, with the occasional diatribe about free agent signings and post-season awards. Thanks to all who followed the Mets season with us this year.

Saturday, October 22, 2005

Then Again...

But my goodness, has there ever been a post season with such horrible umpire errors? (Sorry Angels.) Could the drums for instant replay in baseball start beating in the offseason...

Tuesday, October 11, 2005

The Best Image to Carry Us Through the Offseason

If a picture is worth a thousand words, this one is worth 10,000. It almost (I said almost) makes up for the disintegration of my A.L. team, the Red Sox. It's hard to imagine both the Red Sox and the Yankees not going through major upheavals in the upcoming offseason.

Back in March I predicted a Cardinals-Angels series, and I think I'll stick with that.

Tuesday, October 04, 2005

The Offseason Digest: The Good, The Bad and the Ugly Redux

The Good

1) Pedro Martinez

Could we have expected anything more from this kooky pitcher? Maybe a few more wins if the bullpen had held up its end of the bargain.

2) David Wright

Superstar. Sign him to a long term deal soon.

3) Jose Reyes

Kept getting better as the season went along, AND played 161 games. Getting some more walk and a better eye at the plate, and he’ll definitely live up to all the hype.

4) Cliff Floyd

So the offense was great, but seriously, give this guy a Gold Glove for his work in the field.

5) The catcher’s position

Name another catcher who gave their team 27 home runs and 103 RBI? Exactly. Mike Castro did a great job for us, and they were both pretty good at handling the pitching staff.

6) Tom Glavine’s second half

Oh yeah, that’s the guy who I hated as a Brave. Should have gotten 18 wins this year. Now I actually hope he makes it to the 300 mark.

7) Aaron Heilman/Juan Padilla

I see out bullpen combo for the next few years. Let’s hope Omar and Willie see it.

8) Jae Seo

If he hasn’t solidified a place in the rotation, I guess he needs to never give up any runs to do so.

9) Roberto Hernandez

Old man river, thank you for your efforts this season. Alas, I don’t think he’ll be able to do it again in 2006.

10) Mike Jacobs

Please, don’t be the second coming of Benny or Butch. Keep that sweet swing coming next season.

The Bad

1) Carlos Beltran

Here’s the only positive I see out of this season--there’s no way he could be this bad next year. Unless he’s the next George Foster. (Shudder)

2) The hole we call 2nd base

Goodbye Miguel. Goodbye Kaz. We won’t miss you.

3) The hole we call 1st base

Can’t anyone hit when they play at this position? (Well, we can excuse Mike Jacobs from this discussion)

4) Willie Randolph’s decision-making skills

Please, please, please: don’t keep sticking with “your guys” next year.

5) Kris Benson’s second half

Is this guy just a first half pitcher or what?

The Ugly

1) Braden Looper

Injury or no injury, he might have become more hated than Armando, which I didn’t think was possible.

2) Kaz Ishii/Victor Zambrano

Two mistakes--one by the new regime, one by the old regime. Both need to be put on one-way flights out of LaGuardia.

3) Danny Graves/Shingo Takatsu

There is a reason these guys were rejects. If I see either of them pitch in a Met uni ever again, I will personally go to Shea and kick Omar’s ass.

4) Gerald Williams/Jose Offerman

Why did these guys take up roster space?

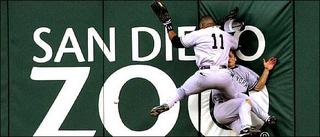

5) The Carlos Beltran/Mike Cameron collision.

Ouch.

So there you go for 2005. I will stick with my prediction for 2006--94-69, with the wild card.

P.S.--Go Red Sox and Angels!

Monday, October 03, 2005

Zisk # 11

Publisher’s Note:

My friend Mike was telling me about a movie he’d recently seen, a 3-D IMAX movie about the moon.

“It was meant for someone who’s never heard of the moon before—there was nothing new. And it turns out there’s not much to see on the moon, a whole lot of dull mixed with a bit of uninteresting.”

That’s a perfect description for the 2005 NL pennant race, a mundane landscape of runaway division winners. Personally, I’m pulling for the Padres to win the NL West and make the post-season with a sub-.500 record; we’ll have plenty to talk about when a losing team wins the World Series—Mets fans in particular given that the Mets are likely to finish last in their division yet still have a better record than the playoff-bound Padres.

Speaking of the Mets, check out the Zisk website for a day-by-day account of the Metropolitans 2005 season. We’ve had a great time covering the Mets every day, but plan to expand the site’s focus during the off-season and into next year. Steve has gone grey trying to come up with different ways to say, “Looper blows another save” and “Beltran left four more runners on base last night” or “Why on earth is Willie sticking with Ishii and Zambrano?!? Please god, tell me why.”

Meanwhile, all the action right now is in the AL, which is bubbling like the surface of a volcano. There are three races coming down to the last week; Los Angeles taking advantage of Oakland’s many injuries; Chicago and Boston trying to avoid collapses that will have their faithful agonizing all winter. The AL can even boast of having baseball’s biggest schmuck, with Rafael Palmeiro passing Barry Bonds.

Here’s to an exciting playoff season. Let anyone but the Yankees win! (Hey, this issue is otherwise devoid of Yankee bashing, we’re allowed a token dig.)

The Quick And the Brain Dead by John Shiffert

The Loser in Right Field by Steve Reynolds

Darryl, Off Broadway by Mike Faloon

Who Belongs in Cooperstown by Jeff Herz

Baseball Returns to Our Nation's Capitol by Nancy Golden

Alex Wolf, Meet the Mets by Greg Prince

My Dad, The Captain of the Cincinnati Reds by Shawn Abnoxious

Prescription For a Post-Season Media Diet by Heath Row

Bat Boy For a Day by Mike Faloon

Hacking at Slop by Ken Derr

The story begins thusly: the Giants home on the radio is KNBR, a 50,000 watt station that reaches north to Oregon, east to the Sierras and south to the immoral confines of Isla Vista, home of the UCSB Gauchos. One night, after another aesthetically repulsive home loss to the Colorado Rockies, radio talk-show host Larry Krueger, an 8-year KNBR employee, went on the air and vented some pent-up frustration, denouncing “brain-dead Caribbean players hacking at slop nightly” and insisting that manager Felipe Alou’s brain was made of Cream of Wheat.

When told the next day of Krueger’s remarks, Alou was livid, arguing that as a young player coming up in the south he had to put up with all kinds of nasty racist comments, and he was not going to stand for it now that he was in a position to call the bastards out. KNBR suspended Krueger for a week, and the media in the Bay Area began sniffing race scandal blood. Meanwhile, Krueger offered to meet with Alou and apologize. Alou refused, insisting that while he did not want to see Krueger fired, people from the countries that comprise the Caribbean “were offended by that idiot. This guy offended hundreds of millions of Caribbeans.” A few days later, things appeared to simmer down, but Alou was still boiling over. In an interview with ESPN’s Outside the Lines, which aired right before Krueger was to be reinstated, he went Old Testament. He called Kruger “this messenger of Satan, as I call this guy now,” and justified his reason for refusing to meet with Kruger this way: “I believe there is no forgiveness for Satan.” And while reporters dug deep to explore Krueger’s reputed youthful obsession with Black Sabbath, a midnight raid to excavate his backyard revealed no bones of eaten children.

After Alou’s “Satan” comments aired, the next morning’s radio hosts, Brian Murphy and (ex-Giant) F. P. Santangelo, were exploring whether the manager’s response was just a bit over the top. Yes Krueger had screwed up and deserved to be punished, but was he really an agent of Beelzebub? At that moment, their young producer, Tony Rhein, hoping to bring a little levity to what was an awkward time for the new morning hosts and trying to put a little mocking sting in Alou, interjected two “samples”: a Dana Carvey SNL church lady cry of “Satan!” and a South Park sound bite from an episode that included a weigh-in before a fight between Jesus and Satan. It was over in seconds (the soundbite that is—no word on the length of the battle between the divinities). That night, KNBR Senior Vice President Tony Salvadore posted a short announcement on the radio’s website announcing the immediate dismissal of Krueger, Rhein and 16-year veteran programming director Bob Agnew. “The segment, featuring inappropriate comedy sound bites,” Salvadore wrote in the statement, “Demonstrated an utter lack of regard for the sensitivity of the issues involved and a premeditated intent to ridicule Felipe Alou’s commentary…KNBR deeply regrets the comments and actions of these individuals, which do not reflect our beliefs or values as an organization. We would like to express our deepest apologies to Felipe Alou, his players and the Giants’ organization for this offense to the Caribbean community.” This missive was placed on the website at 10:15 p.m. What in the name of Jehovah were the talk show hosts going to say the next morning, less than eight hours later, with both their immediate boss and their producer out on the street?

Well, Murphy and Santangelo, who had been with KNBR less than a year, tried their darndest to do radio ballet. It was obvious that they were devastated by the firings, especially that of Rhein, whom they could not stop praising. They also knew that the man who had fired their friends was the man who had hired them and could have their own heads on a block if they went too far attacking management for the decisions. The majority of callers, however, swung verbal mallets. Most attacked the firings, and their two main theories for the cannings can be summarized as such: 1) KNBR laid down for the ultra-liberal Berkeley/SF PC Nazis because it did not want to deal with an assault on the station by the militant wing of the Rainbow Coalition, and 2) The Giants organization demanded the firings to support Alou and, and KNBR laid down. Callers had very few kind words for anyone, and most were seething with outrage. You could hear the spittle dripping from the corners of their blood-drenched mouths.

Esteemed and despised local media personality Gary Radnich was due to take over KNBR’s 9:00 a.m. slot, and Murphy had been insisting all morning that Radnich’s experience and insight would lead us out of the relativist wilderness and into the promised land of moral clarity. Radnich prefaced his remarks with about 14 different qualifications and then stated unequivocally that the Giants organization had nothing to do with the firings. Radnich tied Salvatore’s decision to the fact that KNBR's parent company, Susquehanna Radio Corp. of York, Pa., had been up for sale for several months. That made Tuesday morning's attempt at comedy, at least in the ears of the powers-that-be in York, more than a harmless mistake. “It's another log on the fire,'' Radnich told his listeners, suggesting that if Alou thought KNBR was teasing him and rallied community support, an FCC investigation could hurt the sale of Susquehanna, which operates 33 stations in eight markets. “You’re talking licensing, you’re talking millions of dollars,”' Radnich said. “This is business. And in the end, business wins. That is why Larry Krueger is not with the station anymore.” Radnich refused to blame the Giants, but he did say that Alou’s “ranting and raving are the primary reason this thing reached the point that it did.” He never explained exactly how the licenses were suddenly at risk, but by the end of the day, callers had themselves a new villain, and his name was Felipe Alou. Krueger, in the meantime, had been morphed from a zealous lout who had revealed his latent racism in the heat of a convulsive verbal moment to the Mario Savio of sports radio, a victim of intolerant PC thinskinners and callous corporate bigwigs.

When Alou heard about the firings, he said, “I feel bad about people being fired. It wasn't my intention, but I didn't start it and I took a stand. It was their decision," he said of the station. “Hopefully, they understand that people are not going to sit still and be put down like that. In the USA, I don't believe there is any room for that.” He did not explain, however, how or why it was OK for his organization’s radio station to keep hell’s chief on board. Perhaps Krueger was the tempting snake in the Garden, luring dormant racists up off their lazy boys to eat from the tree of hate. Even theological interpretations, however, weren’t enough for the godless Bay Area, as a poll on the San Francisco Chronicle’s website, taken the day after the firings, showed. Only 21% of the respondents said that Krueger should be fired, while 68% said that termination was an overreaction. KNBR callers continued to scald Alou in the days that followed, while the Giants and KNBR management went quiet, desperately hoping that some SF supervisor would make his monthly egregious faux pas, and we could all go back to hating our secular targets of animosity.

Some three weeks later, the game of black and white hats isn’t so easy, so if you’re looking for ultimate judgments, go watch the 700 Club. Yes, Krueger’s “Caribbean” comment was racist, and if he had been fired immediately (which he probably should have been), the uproar would have been far less intense than it ultimately was. He wasn’t fired, however, but that did not stop Alou from seeking outlets (he went on the local Spanish TV station to attack Krueger in addition to his ESPN interview) to vent his frustration in Biblical terms, all the while insisting he did not want Krueger let go. Perhaps Alou’s support of free speech also applies to denizens of hell, and he was simply trying to let truth win in the public forum, but he never made that clear. The vehemence of his attacks, his unwillingness to meet with Krueger and accept his apology (and perhaps educate the man) and his insistence on Krueger’s satanic connections stole fuel from his legitimate outrage. Everybody understood why the man was pissed, but fewer and fewer felt comfortable supporting him as his mouth continued to roar from the dugout pulpit.

Maybe Radnich was right, and it was all about money. Three weeks after this whole sordid mess broke, however, I can’t help wondering how it would have played if the Giants were above .500 and in first place (as I write, the Padres are one game below .500 and 5 ½ games up in the NL West), instead of stumbling along in 4th place in the weakest division in Major League history. Krueger’s frustration with the wildly underachieving Giants pilfered his judgment, and he went public with something he might secretly believe but would never have aired had the team been winning. I suppose you could also argue that losing actually breeds such ugly sentiments, digging into the darkest recesses of the subconscious and planting such ugliest sentiments, but I’ve always tried to keep Freud out of my baseball. Winning, however, can be a pretty good band aid.

In some ways, the whole Krueger affair has been illustrative of the Giants season—one dumb move after the next, with good judgment and timely speaking decidedly missing in action. So, three guys are out of a job, Felipe Alou has lost the respect of many of his former fans, KNBR’s reputation is stained, and I’m sitting here still trying to figure what the hell happened to the season.

You know, maybe I do have a solution to this whole mess—why don’t we all just blame Barry? If he had been around, everyone could have been focusing their antipathy on his barcalounger, denouncing his cream and cleared accomplishments, and abominating his every breath. Hell, we’d all be too tired to stay up for late-night talk radio, and with Barry around, hey, maybe we just might be creeping up to that .500 mark. And let’s face it—if ever there was a messenger of Satan…

Ken Derr is a San Francisco Giants fan and is really looking forward to hockey season. Go Sharks!

The Quick And the Brain Dead by John Shiffert

Steve Bellan was born into a Cuban (not Spanish) family in Havana in 1850, and was playing baseball at its highest level in the U.S. by the time he was 18, first with the Unions of Morrisiana, and then, for the next four years, with the Troy Haymakers. He finished his American career with eight games with the New York Mutuals in 1873. Thus, Bellan spanned the period between the National Association of Base Ball Players and the first professional league, the National Association. Basically a good-fielding third baseman, though with a scatter arm, he was only a fair hitter (.252 BA) with little power, although he did have a 5-for-5 day with five RBIs against Al Spalding on August 3, 1871. He was also eighth in the National Association in walks in 1871, drawing nine (the rules provided for very few walks in this era) in 29 games.

When he returned to Cuba, he was among the first to introduce baseball there, and he participated in the first organized baseball game in his native land in 1874. Apparently, he found some power back home, because he hit three home runs in a game on December 27, 1874. Bellan later went on to become the player-manager of the Havana team from 1878 to 1886 and lead his squad to championships in 1878-79, 1879-1880 and 1882-83.

The trend that Bellan helped start would make baseball as big a sport in Latin America, especially the Caribbean, as it is in the United States. By the start of the 21st Century, hundreds of thousands of Caribbean natives had taken up the game, and an increasing number were not surprisingly coming to America to get ahead and test their skills…just like Steve Bellan did almost 140 years ago.

The controversy is… how many of those thousands of Caribbean players are brain-dead? An absurd question, but the subject was brought up approximately 73 years after Steve Bellan’s death by KNBR radio’s now-fired Larry Krueger. Now, KNBR is the flagship station for the San Francisco Giants, and it seems as if Krueger was getting frustrated with the G’ints lack of success at the plate (and in the standings) this year, generating a rant that included a statement about the Giants club and its “brain-dead Caribbean hitters hacking at slop nightly.” This sort of cultural stereotyping is, of course, an anathema to most people, and it quite naturally provoked a firestorm of controversy, especially with Giants’ manager Felipe Alou, who happens to be from the Dominican Republican (remember the old saying attributed to Dominican players, “you can’t get off the Island by walking?”) and who also happened to object to being characterized in the same rant as a “manager…whose mind has turned to Cream of Wheat.”

All well and good, or maybe bad. But, what about the actual statistics that may or may not support Kreuger’s assertion? (The walking comment, not the Cream of Wheat comment.) In the fallout over Kreuger’s manifestly politically incorrect statement, no one seems to have wanted to explore the facts. Possibly out of fear of also being characterized as politically incorrect. Well, Zisk has no fear, so we’ll ask the question—do Caribbean players indeed lack plate discipline? That’s something that can be studied dispassionately, through the baseball record. First, let’s look at the 2005 San Francisco Giants, and their relevant stats, as of the time that Kreuger made his ill-fated rant:

AB W OBP ID

Giants 3769 313 .326 .060

Opponents 3810 408 .345 .082

It seems pretty obvious that the Giants as a team were not drawing walks at a rate anywhere near their opponents—almost 100 fewer walks, and on-base percentage almost 20 points lower, and a team Isolated Discipline (On-Base Percentage minus Batting Average) 22 points lower. Now, how much of that can be laid at the feet (or heads) of their Latino players?

In early August 2005, there were five Giants who were born in Caribbean nations who had more than 100 plate appearances in 2005:

AB W OBP ID

Pedro Feliz 401 26 .309 .042

Omar Vizquel 390 36 .350 .060

Edgardo Alfonzo 258 21 .349 .054

Deivi Cruz 185 9 .299 .034

Yorvit Torrealba 93 9 .301 .075

A mixed message at best. Vizquel and Alfonzo had on base-percentages significantly better than the team’s. Torrealba was the only one to meet the Rule of 10 for Walks (having around 10% as many walks as at bats) and had a better Isolated Discipline (ID—a stat developed by your humble author and derived by subtracting batting average from on base percentage) than the team, while Vizquel was right at the team ID average and actually had more walks than strikeouts. Collectively, these five players had an on-base percentage of .328, just about the team average. So, you could say that, while they were not part of the solution, they also were not really part of the problem—they were just part of a team that didn’t draw many walks.

It should be noted that this accounting does not include Moises Alou, son of Felipe, who was born in Atlanta and raised in the United States, and who happened, at the time, to be by far the team’s best hitter, with a .925 OPS. Maybe it’s a coincidence, but his figures at the time were as follows:

AB W OBP ID

Moises Alou 302 46 .418 .090

(An aside: I saw Moises Alou play in a New York/Pennsylvania League game at, of all places, Doubleday Field in Cooperstown, when he was about 18 years old. He spent the entire afternoon futilely chasing curve balls in the dirt.)

Obviously, this study says more about the 2005 Giants than it does about Caribbean players as a whole. It only covers six members of one team for a part of one season. What about the big picture, over a much larger slice of baseball history? The four Caribbean countries that have provided major league baseball with by far the most players in the last century have been the Dominican Republic (385), Puerto Rico (214), Venezuela (169) and Cuba (148). Let’s take a look at all the players from those countries who have had significant careers. In this case, 6000 plate appearances or more, or the rough equivalent of 10 full seasons, and ranked by ID.

Dominican Republic

AB W OBP ID

Manny Ramirez 5948 928 .409 .095

Jose Offerman 5652 766 .360 .087

Sammy Sosa 8362 895 .346 .071

Rico Carty 5606 642 .369 .070

Pedro Guerrero 5392 609 .370 .070

Julio Franco 8363 882 .366 .066

Cesar Cedeno 7310 664 .347 .062

Tony Fernandez 7911 690 .347 .059

Raul Mondesi 5814 475 .331 .058

Juan Samuel 6081 440 .315 .056

Tony Pena 6489 455 .309 .049

Felipe Alou 7339 423 .328 .042

Julian Javier 5722 314 .296 .039

George Bell 6123 331 .316 .038

Matty Alou 5789 311 .345 .038

Alfredo Griffin 6780 338 .285 .036

(Hmmm… maybe that’s why Felipe Alou was so upset. By the way, Jesus Alou’s career ID was an awful .025.)

Puerto Rico

AB W OBP ID

Carlos Delgado 5368 872 .392 .109

Bernie Williams 7278 1024 .385 .086

Roberto Alomar 9076 1032 .371 .071

Jose Cruz, Sr. 7917 878 .354 .070

Orlando Cepeda 7927 588 .350 .053

Willie Montanez 5843 465 .327 .052

Juan Gonzalez 6555 457 .343 .048

Benito Santiago 6951 430 .307 .044

Felix Milan 5791 318 .322 .043

Roberto Clemente 9454 621 .359 .042

Ivan Rodriguez 7076 406 .345 .039

Vic Power 6046 279 .315 .031

Cuba

AB W OBP ID

Minnie Minoso 6579 814 .389 .091

Jose Canseco 7057 906 .353 .087

Raffy Palmeiro 10446 1351 .371 .082

Tony Perez 9778 925 .341 .062

Tony Taylor 7680 613 .321 .060

Jose Cardenal 6964 608 .333 .058

Leo Cardenas 6707 522 .311 .054

Bert Campaneris 8684 618 .311 .052

Tony Oliva 6301 448 .353 .049

Cookie Rojas 6309 396 .306 .043

Venezuela

AB W OBP ID

Omar Vizquel 8213 822 .341 .066

Andres Gallarraga 8096 583 .347 .059

Dave Concepcion 8723 736 .322 .055

Manny Trillo 5950 452 .316 .053

Luis Aparicio 10230 736 .311 .049

Ozzie Guillen 6686 239 .287 .023

What, if anything, can we learn from these 44 players? First, that this is an arbitrary cut-off point. If we were to include all those players with 5000 plate appearances then, for instance, you could add Bobby Abreu, a master of controlling the strike zone, to the Venezuela list, and his numbers look like this:

AB W OBP ID

Bobby Abreu 4559 843 .411 .107

Cutting back to 5000 career PAs also brings in Danny Tartabull (Puerto Rico), with his .095 career ID, Stan Javier, who had a lot more plate discipline than his dad (.076), and another Venezuelan, Alfonzo, who’s actually having a bad year in 2005, because his career ID is .073. On the other side of the coin, Caribbean players with between 5000 and 6000 PAs also include Cuba’s Tito Fuentes (.039), Venezuela’s Tony Armas (.035), Dominican Rafael Ramirez (.034) and Puerto Rico’s Carlos Baerga (.040), so maybe it balances out.

Of more significance is a point made by the exceedingly astute Bill Deane, the former National Baseball Library researcher and a Hall of Fame thinker on the sport. Deane notes that while Latino players, “had been taught early on that the only way to attract the attention of major league scouts was by their hitting ability, not their patience; so, their only hope to leave their native islands for the promised land of the majors was to go up there hacking.” However, Deane makes another, more important point—this trend has changed in recent years, in that, prior to 1999, only one Latin-born player (Tartabull) had ever drawn 100 walks in a season. Since then, notes Deane, it’s become fairly common, thanks to the skills of—among others—Abreu, Williams, Delgado, Palmeiro and Jorge Posada.

The thought also occurs that some of these players, though born in Caribbean nations, weren’t raised there. Ramirez (who went to high school in New York), Canseco (Miami), Palmeiro and Alomar come quickly to mind. Still, overall we can say we’re looking at a pretty good-sized sample of players with long-time major league service starting about 50 years ago. Meaning, among other things, that they had to be considered at least pretty good hitters to have stayed around that long, with the possible exceptions of Javier, Griffin, Milan, Power, Rojas and Guillen, who were perhaps better known for their work in the field. Of course, the perceived value of a base on balls has never been higher than it is today. Back in the ’50s and ’60s, a walk wasn’t generally considered as good as a hit, so maybe you could last longer, even if you didn’t walk much.

Maybe the best thing is to look at the long-term historical perspective. Over the 50 seasons from 1955 to 2004, which basically encompasses the careers of all of these players, the average ID in the National League was .064, and, except for a couple of years in the “New DeadBall Era” of the 60s, it really hasn’t varied very much from that median. Over those same 50 seasons the average seasonal ID for the American League as a whole has been a bit higher, .067, although, once again, there hasn’t been much variance from that standard over the years, with the yearly marks rarely dropping below .060, and then not very far below .060. Thus, we can say that 14 of our 44-man sample had career ID’s above the National League standard and 12 had career ID’s above the American League standard. (The two that fell between the American and National League averages are current players Omar Vizquel and Julio Franco.) And, if we recall The Rule of 10 for Walks, we also see that just 14 of the 44 (Ramirez, Offerman, Sosa, Carty, Guerrero, Franco, Delgado, Williams, Alomar, Cruz, Minoso, Canseco, Palmeiro, Vizquel) meet that standard, that is, only 14 of these players had walk totals that were within 10% of their at bats. However, also note that, in conjunction to Deane’s point, that Ramirez, Offerman, Sosa, Franco, Delgado, Williams, Alomar, Canseco, Palmeiro and Vizquel are current or recent players.

Individually, only Carlos Delgado on this list (as well as Abreu, once he gets 6000 PA) qualify as ID Monsters, with career IDs over .100. Whereas, any pitcher who walked Ozzie Guillen should have been pulled from the game immediately. Ditto for Javier, Bell (even though he was a power hitter), Matty Alou, Griffin, Rodriguez and Power. Actually, power hitters (as opposed to Vic Power) are scarce on these lists. That may be a significant point, since power hitters will typically get more walks from pitchers just pitching around them. Only Canseco, Palmeiro, Perez, Gallarraga, Bell, Ramirez, Sosa, Cepeda, Delgado and Gonzalez would unanimously make anyone’s list of power hitters, and only Bell and Juan Gone of that group really have seriously (more than 10 points below average) sub-par IDs. So, it could be postulated that Caribbean players seem like they draw fewer walks because there are relatively few power hitters in their grouping.

What does this all mean? What’s the conclusion? Well, another deep thinker on the game, Matt Coyne, has pointed to an interview Panamanian Manny Sanguillen (he of the .030 ID in 5300 PAs) gave years ago where the writer made a point of saying that Latin players would swing at anything because each time at bat was so valuable and that it was a macho thing to hit, meaning that only a nancy boy (Coyne’s term—an anachronism from his youth in the mid-19th Century) would accept a walk. So, maybe there’s something to the theory that Caribbean players don’t walk that much, at least up until 1999. Does that make them brain-dead hackers? Or, for that matter, does that make Rocco Baldelli a brain-dead Italian hacker? Hardly.

John Shiffert is the author of Baseball: 1862 to 2003 [PublishAmerica, 2004] and the forthcoming book, Baseball…Then and Now [PublishAmerica, 2005]. His third book, on Philadelphia baseball in the 19th Century will be published by McFarland in 2006. He can be reached through his website, www.baseball19to21.com.

The Loser in Right Field by Steve Reynolds

Now I liked baseball as much as any 11-year-old kid did. I started collecting cards in 1977, spurred on by my grandfather Ray. Ray Reynolds was a hard working man throughout his whole life. He spent over 30 years working for the New York State Department of Transportation, sweating over blacktop in the summer and spending long hours plowing the voluminous amounts of snow that fell over the Berkshires each winter. Beyond that job, he worked weekends and evenings as a caretaker at the estate of city stockbroker, breaking his back pulling weeds, planting flowers and vacuuming the pool.

So when he actually had time off, he liked to watch other people work hard, hence his love of baseball. He was a Dodgers fan to the core, and when I started showing interest in baseball (my first TV memory is watching Henry Aaron’s 715th home run), he tried to instill that same Dodgers passion in me. While I did root for them in the playoffs and World Series, I somehow became a fan of baseball’s other lovable losers—the New York Mets and Boston Red Sox, just because we could actually see their games on broadcast TV once in a while. (Of course, picking those teams was just the first of a long line of misguided decisions, but that’s a story for another time.)

In the end, my grandfather didn’t care who I rooted for or against. He was just happy that he could share his passion for baseball with me. I was raised by my grandparents and my aunt, and since my grandfather was retired by the time I became passionate about baseball (and, more importantly, baseball cards) he would always drive me to Zayre’s to get cards and some candy for both of us. (Gee, thanks for the lifelong gut, Gramps.) As I look back on that time, I also think my grandfather liked to come up with reasons to drive me around just to get away from his domineering bitch of a wife, my grandmother Emma. When people tell me I have a rather loud voice, I feel like telling them it’s because yelling was the only way to talk to my grandmother. She yelled at my grandfather for ruining my diet, for buying those “useless pieces of paper,” for being late for dinner, for messing up the house and heck, she probably yelled at him for causing the Vietnam War for all I know. This woman loved yelling seven days a week, and as she got older she lost her hearing, so yelling became the trendiest thing we did in our house.

My grandfather died in late 1978, and I’ve always wondered if it really was his heart finally giving out, or that his ears just couldn’t take that loud piercing voice anymore. So when the 1979 baseball season rolled around, my aunt Joyce picked up the sports slack, allowing me to spend my allowance on baseball cards each week. And my grandmother played her part as well, coming up with multiple versions of the word “stupid” to describe my card habit. And that little drama triangle was played to perfection for the next two years.

Then in May 1981 my aunt hit upon a great way for me to lose weight—why just watch baseball when you could be out there playing it with kids my own age? Why be immersed in stats on the back of the cards when I could make some of my own? At the age of 11, I was certain of a few things: The Empire Strikes Back was the greatest movie ever; Legos could only be taken apart with your teeth; The Beatles’ Red Album was the best album ever...and I was horrible athlete. Every single gym class where teams had to be picked, I was always last picked. And with good reason—I couldn’t kick, I couldn’t hit, I couldn’t shoot and I couldn’t even block, even though I outweighed most of the kids in my class.

Yet my aunt saw me crush the wiffleball when I played with my cousins in the backyard, so she thought I could be a great hitter. (Those great eye-hand coordination skills were better used once I got an Atari the next year.) So one night over dinner she announced that she was going to take me to the little league tryouts the next night. I barely had a chance to register my shock when my grandmother offered up some helpful advice: “He can’t hit, he can’t throw, he can’t run. The best thing he could do is maybe eat the ball.” (Wait, I think I meant to say she offered up some painful insults. Yeah, that’s more like it.)

Undaunted by my grandmothers’ criticism (which, in hindsight, I think was delivered at a volume that would drown out the planes flying over Shea), my aunt took me to the tryouts the next night. Hillsdale was a small town, with a population of just barely 800 people, with one traffic light, one supermarket, one liquor store and two thriving bars. (What else are you going to do in rural upstate New York?) So the “tryouts” were basically “show up and we’ll get your kid on the team.” And befitting such a poor town (even though there were plenty of city folks with big summer houses in the town), the Hillsdale little league field looked as though someone designed it to be a living cliché of a piss poor field. Home plate had cracks in it, and if any of us kids really learned how to slide we could have broken it in two. Centerfield was so brown and devoid of grass that I thought it was a reasonable facsimile of the desert planet in Star Wars. And the backstop must have been used in a Rustoleum ad to show what happens in the rain when you didn’t use that all-powerful aerosol can to protect your metal.

But the field had nothing on the rough shape of our coach, who immediately made me think of that drunk guy from The Tonight Show, Foster Brooks, crossed with an overweight version of Tom Selleck on Magnum P.I. Coach van Alston (I never heard his first name the entire season) seemed to slur his words when he welcomed us to little league, and continuously rubbed his moustache as if he was going to find some leftover food (a leftover meatball, perhaps?) buried in its immense bushiness. (And when I turned 17 I realized my Foster Brooks analogy was spot on, as when I got my first smell and swig of whiskey I immediately thought of Coach van Alston and the way he smelled during our Thursday night games.)

I never understood why this man was our coach. None of his kids played on the team. As he was running the tryouts I’m pretty sure he actually dozed off—while standing straight up. I think I saw his brain attempt to crawl out of his ear whenever he was talking with a parent about their child. His assistant coach, Mr. Albright, wasn’t much better of a role model. He looked like he never met a doughnut he didn’t like (which I guess made him my role model) and couldn’t hit ground balls to our infielders any better than I could.

With all this talent supporting me at the tryouts, you can draw only one conclusion—I was HORRIBLE. Any nuances of the game those two “teachers” passed along during that two hour initial tryout went in one ear and out the other. I could grasp any math problem in seconds, had an unhealthy interest in history for someone so young and could easily sing the lyrics to almost any Top 40 hit from 1973 to the present day, yet none of these skills helped as I swung at the first pitch from Mr. Albright…and forgot to hang onto the bat after I swung. That aluminum bat flew about 20 feet, hitting the backstop first and then clanging onto the ground. Every parent stopped in the tracks and immediately looked to make sure their child wasn’t hit by that flying hunk of metal. I learned how to hang onto the bat quickly after that, not that I made any contact. With each miss I racked up, Mr. Albright threw slower, then slower and then delivered what could only be described as an “eephus” pitch. I swung so hard at that one I twisted like a corkscrew and fell right to the ground.

As I picked myself up off the ground I heard the chuckles of my soon-to-be teammates, Coach van Alston walked over to me and said—with a hint of disgust or bemused resignation, I’m not exactly sure which—“That’s okay, kid. We’ll use you as a defensive replacement.” Unfortunately for both of us, coach had seen me attempt to catch fly balls. I never failed to lose sight of the ball when it was at its highest point and ended up using my glove to protect my face more than a place where the ball could safely land. Alas, we were a small town, so everyone made the team.

As the season got underway, I was rightfully buried at the end of the bench, the sixth outfielder on team that probably only needed four. Even with the less-than-professional coaching, our team somehow started out well, going 6 and 2 in our first eight games. I contributed by, well, keeping splinters out of the asses of my more talented teammates. My aunt would always hope I would get into the game, yet she didn’t seem that surprised when I rode the bench all the way through the 7th inning. She knew I stunk, yet would always put a positive spin on it. And she was popular with the other parents, and even ended up umpiring our eighth game when the other umpire couldn’t make it. “Great,” I thought. “My aunt has spent more time on the field than I have.” (She was so successful that night that someone that ran the league asked her to umpire a couple of other games, and then she ended up working the All-Star game we had against one of the other leagues in our county. The ribbing I got for that was a perfect exclamation point on the entire summer.)

At the beginning of July, I caught my lucky break. Two of our backup outfielders were going on vacation over a two week span, so only one kid stood between me and my first appearance in the field. And during a game against Copake my chance came. We were up by four runs, so in the top of the seventh Coach van Alston came over to my usual spot on the bench and said, “Reynolds (buuuuurp), you’re going in into right field.” I grabbed my glove and sprinted out to my position. And then I realized I had NO IDEA how to play my position. I had stopped paying attention in practices at that point when I realized Coach van Alston was more interested in seeing how many Marlboros he could smoke around a bunch of kids in an hour. I started panicking. How do I catch the ball? If it rolls on the ground to me, who do I throw it to? Do I have to crash into that fence behind me? What if I have to go to the bathroom?

“Hey, get on in here!”

I snapped out of my panicky daydream to see that our pitcher had struck out the side and that the game was over. Whew, I dodged a bullet there.

The next game I didn’t play, which left us with only one more game where we didn’t have the full outfield. We were playing Ancram on our home field. Ancram was led by pitcher Nicky Dolan, who shared the same age as I did, but that was about it. Nicky seemed to be seven feet tall, had huge arms and legs, longish hair and generally looked like the size of Chewbacca to me. Nicky not only had a wicked fastball, but he also had the pitch we had all heard about—the curveball. We were battling Nicky’s team for the league lead, so I was convinced that I was never going to get into this game.

When we got to the field, Coach van Alston said to me, “Tom’s not feeling well, so you’re our fourth outfielder tonight.” I never felt so nauseous so quickly. I definitely was going in if we changed pitchers, which meant I’d probably have to face Nicky. Uh-oh. This did not sound good at all. My usual summer sweating kicked up to a level that could have flooded our entire town. I spent each inning watching my teammates flail at Nicky’s Nolan Ryan-esque fastball and his God-like curve for five innings. In the top of the sixth Ancram broke the pitchers’ duel, roughing up our ace Garret for three runs and making the score 4-1. So coach changed pitchers, sending in Richie, who was in right field, to pitch the rest of the game, and sending me out to my own field of nightmares.

Richie struck out the last Ancram batter, so we went into the bottom of the sixth down by three. As I sat on the bench, Mr. Albright said, “Steve, grab a helmet and a bat, you’re leading off.”

Gulp.

Defending my precious head from a towering fly ball with a glove was one thing; having a ball thrown directly at me was NOT what I signed up for. But my aunt was excited to see me up at the plate—she even had her camera out. So I licked my lips (which strangely felt like sandpaper), put a helmet on and grabbed the lightweight red bat that none of my teammates liked to use. With each step to the plate Nicky grew six inches taller, until he finally was tall enough to block out the fading sunlight. I stepped into the batter’s box hoping for one thing—that it would a quick embarrassment for me. Most of my other teammates looked pretty bad swinging at this guy’s pitches, so I figured my incompetence would blend right in.

I stared at Nicky, wiggling my bat from side to side because I thought it looked cool, waiting for that first pitch. When I saw it leave his hand I thought, “Wait, I can hit this.” So I swung. HARD. And missed. HARD. So hard that the bat yet again flew out of my hands—and right past Nicky. My teammates laughed, as they had seen my batting prowess before during practice. But Nicky, well, he looked PISSED. He had a look of, “How dare you try to show me up?” I wanted to yell out, “I’m sorry—can I just go sit on the bench now?” Mr. Albright ran onto the field, picked up the bat and brought it back to me. He said just three words to me: “Hang onto this,” and grumbled on his way back to the coach’s box.

I stepped back into the batter box and thought, “Okay, I’m not going to swing. Just throw two strikes and I will be out of your way forever.” Nicky looked in at me, and I knew he was going to throw a 100 mph fastball. What I didn’t expect is that he’d want to throw it so hard that he gripped it so tightly that the ball slipped out of his hand at the last second—and headed directly for me. Now I didn’t think he would throw at me on purpose; I mean, this kid had pinpoint control for a little league pitcher. His team was cruising. There was no need to settle a score. All these thoughts blinked across my brain, followed by, “Holy crap, I better move.”

Too late.

The 128 mph fastball nailed me as I was trying to turn away, hitting me directly at the top of the spine. I felt like I’d been shot by a high-powered cannon. I was out for just a few seconds, and then rolled over to see my aunt with an extremely worried look on her face—and a look on Coach van Alston face’s that said, “Crap, I hope I don’t get sued for this.” My aunt was a nurse, so she looked at where the ball had hit me and asked me if I could feel everything. And of course I could, especially the hundred eyes looking at me in the dirt surrounding home plate. After a couple of minutes I finally staggered to my feet to take my base. Coach van Alston said, “Good job getting on base kid,” and then—and I swear he did this—gave me a couple of pats on the back where I had just been hit.

When I reached first base I looked at Nicky, who was talking with Ancram’s coach. And he looked as if he’d just left a showing of Friday the 13th Part 2. He was as white as Jason Voorhees’ hockey mask (before all the blood got splattered on it), nervously shifting his feet and kicking the dirt mound. My teammate that followed me to the plate was this big kid named Ricky who I rode the school bus with every day. Any coach with half a brain would have taken Nicky out, but Ancram’s coach came from the old school—sports are not for crybabies. Nicky wasn’t crying, but his mean mound demeanor was certainly gone. His first pitch to Ricky was in the dirt. The second Ricky crushed for a home run. I started running when I heard the “ping”—and immediately fell down, bringing laughter from both teams. I got back up and started running again, but then realized that I could jog home because that ball was never coming back.

Alas, we didn’t win the game. The Ancram coach replaced Nicky with his younger brother, and he shut us down in order to close it out. I didn’t play another inning the rest of the season. We finished second in our league to Ancram, with no help from me. (Even though I did have a perfect on base percentage.) When we lost our final game to Ancram, I distinctly remember overhearing Nicky saying, “Well, at last they didn’t put in that loser in right field. He couldn’t get out of the way of his own shadow.” I was never happier to leave a ball field than that day. I knew, as did my aunt, that I did not belong anywhere within the confines of a baseball diamond. My love of the game was destined to lead me some place more comfortable than right field—the upper deck at Shea.

Steve Reynolds is the co-editor of Zisk, and admits that he probably couldn’t hit a fastball thrown by any 11-year-old today.

Who Belongs in Cooperstown? by Jeff Herz

Let me start with some broad categories of players who do not belong in the Hall: 1) Mediocre or above average players, who might have had a few good years, but have not performed over the long term, do not belong; 2) Compilers, players who played beyond their years even though their statistics continued to fall, hanging on to reach some individual goal that baseball anointed as being a H-O-F credential, don’t belong. Quite simply, was the player among the elite players of his day. If yes, then you can argue he should be in the Hall. If you can name two or more players better then that player at the same position, then I would argue that the player in question should not be in the Cooperstown.

The Hall-of-Fame should be reserved for the best of the best at the time they played the game; those individuals who performed almost every year of their career significantly above the league average. In the Rocketball Era averaging 30 home runs a year does not make you a Hall of Famer since so many players have routinely hit 50+ in that same time frame. The bar we use to measure players’ performances needs to be moved up or down over time based upon the level of competition, the ball parks, expansion, and many other factors.

I am not even going to discuss players in the “No Brainer” category. They’re locks for the Hall. (But with future fallout regarding steroids use, possible exceptions to this category are noted with **.) The position players are Barry Bonds**, Tony Gwynn, Cal Ripken, Alex Rodriguez, Rickey Henderson, Sammy Sosa**, Mark McGwire**, Ivan Rodriguez and Mike Piazza. The pitchers are: Roger Clemens, Randy Johnson, Greg Maddux, Mariano Rivera and Pedro Martinez. That’s 10 position players and five pitchers, which tells me we are currently living in a hitters’ world, and with the common routine being starter for five or six innings, middle reliever, closer, I am not sure we have enough perspective to truly evaluate pitchers during this time period beyond the five mentioned above. It’s a topic that merits its own discussion.

When I review the list of top eligible pitchers not listed above I come up with the following Lee Smith, Jim Kaat, Rich “Goose” Gossage, Jack Morris and Bert Blyleven. The active pitchers are Tom Glavine, Curt Schilling, John Franco, Trevor Hoffman and John Smoltz. The hitters included the following retired players Jim Rice, Don Mattingly, Steve Garvey, Dave Parker, Ted Simmons, Joe Jackson (ineligible), Alan Trammel, Andre Dawson and Dale Murphy. It is interesting that Ron Santo, who is the latest HOF media darling not enshrined, is a whole 20 Jamesian points behind Andre Dawson, so not worthy of considerations. Along with the following active players Ken Griffey Jr, Roberto Alomar, Frank Thomas, Rafael Palmeiro**, Manny Ramirez, Todd Helton, Larry Walker, Jeff Bagwell, Bernie Williams and Vlad Guerrero.

They are all good, but are they great, are they good enough to be immortalized in Cooperstown?

Let’s briefly look at each person and see why they do or do not belong. (Author’s note: I am using baseball-reference.com as the basis for my comparison and providing the players statistics. All stats are through the 2004 season)

Lee Smith – 136 HOF points*, 478 saves, 1289 IP; Rich “Goose” Gossage – 126 HOF points, 310 saves, 1809 IP -With closers Rollie Fingers and Dennis Eckersley now in the Hall of Fame, and Mariano a foregone conclusion, I think it is time that Smith and Goose get their due. In order to save a game during this era, closers were often asked to work two or three innings. Today a closer is working one inning or less most of the time outside of the playoffs, and therefore are less valuable than Smith and Gossage were. My vote: IN

Jim Kaat – 129 HOF points*, 283 wins, 2461 K’s, 4 WS Appearances, 3 20+ win seasons - Kaat was solid for 25 years, never a team ace, never a standout season that brought him high votes in the CY Young or MVP voting, Conclusion: Compiler, My vote: OUT

Jack Morris – 122 HOF points*, 254 wins, 2478 K’s, 3 WS Appearances -3 wins, 3 20+ win seasons - Morris was the ace of the Tigers for years, leading the AL in wins for the entire decade of the 1980’s. He played for and was the ace of three World Series winning teams with the ‘84 Tigers, the ‘91 Twins, and the ‘92 Blue Jays. He was a gritty and determined, and pitched 10 innings of perhaps the greatest individual World Series game in history, Game 7 in 1991 against John Smoltz and the Braves. Morris is HOF caliber and should be voted in. My Vote: IN

Bert Blyleven – 120 HOF points*, 287wins, 3701 K’s, 2 World Series Appearances; one word describes this Dutchman, Compiler. My vote: OUT

Tom Glavine – 154 HOF points* 262 wins, 2245 k’s, 5 20 wins Seasons, 4 WS Appearances – 1 win, Curt Schilling 151 HOF points*, 184 wins, 2745 K’s, 2 20 win seasons- I am going to group Glavine and Schilling together, because I think they are both gritty competitors and both the Braves in Glavine’s prime and, for Schilling, the D’back’s in 2001 and the Red Sox in 2004, were better because of them. But would Glavine have been as good on a different team? Also, I think the fact that Schilling was traded so many times devalues his statistics. In order to be in the HOF, you need to have a great career, not just a few good years, and few great years, and both of these fit this category: My vote: OUT

John Franco – 126 HOF points*, 424 saves, 1230 IP, Trevor Hoffman – 100 HOF points*, 393 saves 764 IP- In spite of my previous efforts to bring in Smith and Gossage, I don’t think Franco or Hoffman are good enough to make the cut. They have both totaled many saves, but not many innings, and not with much dominance. I view Franco as a compiler, and Hoffman as simply not having what it takes to make the Hall. My vote: OUT

John Smoltz – 128 HOF points*, 163 wins, 154 saves. – I am going to withhold judgment on Smoltz until his career is completely over, since he went from starter to closer back to starter, which is quite impressive. If he is able to pitch dominantly as a starter for a few more years as he has so far this year, then I would say he could be considered great and should be in. We’ll see.

Jim Rice, Don Mattingly, Steve Garvey, Dave Parker, Ted Simmons, Alan Trammel, Andre Dawson, and Dale Murphy are quite simply all good or very good players who might have excelled in their positions for a few years, but were never great for an extended period of time. Quite simply the BBWA got these right, as amazing as that seems. My vote: OUT

Joe Jackson (ineligible) – this is a whole different story. See previous Zisk article on the concept of a lifetime ban, and the fact that Jackson lifetime ended in 1951, and therefore should be eligible for consideration. My vote: IN

Ken Griffey Jr – 204 HOF points*, 501 HR’s, 2156 hits – Once considered a sure thing, but injuries have derailed his career for the past few years and have brought his credentials into question. I think he was sufficiently great enough for a long enough period of time, and the injuries, which I attribute to lack of conditioning should encourage voters to believe he was not on the juice, just lazy in the off-season and relied on natural talent, which faded in his thirties. Even still, I think he is still a good bet. My Vote: IN

Roberto Alomar – 193 HOF points*, 2724 hits – perhaps the premier 2B of the post Ryne Sandberg generation, which includes Craig Biggio and others. However, I will forever remember him for spitting on an umpire and tarnishing the game. He has also been traded multiple times and played for a total of seven teams in 17 seasons. I know I never mentioned team loyalty as a criteria for HOF eligibility, and in today’s game it is impossible to assume a player will be with one team for his entire career, but this type of activity is a bit concerning. Still, my vote: IN

Frank Thomas – 179 HOF points*, 436 HR’s, 2 MVP’s, 15 seasons, 2113 hits .308 BA – Thomas creates the most difficult player in this article. Mostly I remember him as being a run down, injury prone, cranky White Sox DH. However, he was probably the premier player in MLB during the 90s. Better than McGwire, better than Boggs, better than Gwynn. He is going to be perceived a lot like Don Mattingly, great early on and injured later on that hurt his credentials. I think that Thomas is vastly superior to Donnie Baseball, but I am concerned writers will only remember his recent past, and not the monster he was in his prime. My vote: IN

Rafael Palmeiro** - 156 HOF points* - Just because a player accumulates 500 HR and 3000 hits in this era, does not make them great, and Raffy is a perfect example, even before his recent steroid suspension (which has even further clouded his ability to compile statistics since steroids allegedly help keep players healthy and he has never been on the DL in 19 seasons). I have to group him with Fred McGriff, a guy who played a long time and compiled some good looking stats, but was never the premier player at his position during his career. My vote: OUT

Manny Ramirez – 155 HOF points*, 12 seasons, 390 HR’s – Manny is Manny as they say. I think he is special. I hate him because he has played for the Indians and the Red Sox, the Yankees’ largest rivals the past 10 years. Manny is a questionable fielder and a defensive liability. He is best suited to be a DH, and I don’t think DH’s should be in the Hall (see Paul Molitor). In spite of this, he still plays left field in Fenway, and make the occasionally gaffe. All of this can be forgiven, because he is an incredible offensive force. He is consistently among the leaders in all major hitting categories. My vote: IN

Todd Helton, Larry Walker, Jeff Bagwell, and Bernie Williams – They all have had flashes of brilliance, but not one of these players is consistently great. My vote: OUT

Vlad Guerrero – 134 HOF Points*, Let’s wait and see how he finishes his career before giving him the benefit of the doubt, though he is well on his way, hopefully he follows the A-Rod route (in spite of no significant post season results) and not Griffey’s.

In conclusion, and as much as I hate to admit it, the BBWA has been right in their voting up until now. I would like to see Morris, Smith and Gossage in Cooperstown. I don’t see any glaring mistakes when it comes to batters that are eligible that are not in yet. I think many current players are playing in small stadiums, in an era where steroids and diluted pitching has inflated the numbers making average players look above average, and making historical comparison difficult if not impossible for the non-mathematicians.

Among current players, only a handful are truly great, and should be referred to as certain Hall of Famers. The rest are good, but not great and have made very good money playing a kids game and should be happy with their successful careers, and should not hold their collective breath awaiting a call from the Hall.

Jeff Herz is an Information Technology manager who lives in CT works in NYC and loves baseball and baseball history. He has began writing a blog, which can be found at herzy69.blogspot.com. He is also a collector of baseball and football cards, so if you got any to trade, let him know.

A Hall of Fame Points

*HOF Points are another Bill James creation. It attempts to assess how likely (not how deserving) an active player is to make the Hall of Fame. Its rough scale is that 100 means a good possibility and 130 is a virtual cinch. It isn't hard and fast, but it does a pretty good job. Here are the rules:

Hitting Rules

For average, 2.5 points for each season over .300, 5.0 for over .350, 15 for over .400. Seasons are not double-counted. I require 100 games in a season to qualify for this bonus.

For hits, 5 points for each season of 200 or more hits.

3 points for each season of 100 RBI's and 3 points for each season of 100 runs.

10 points for 50 home runs, 4 points for 40 HR, and 2 points for 30 HR.

2 points for 45 doubles and 1 point for 35 doubles.

8 points for each MVP award and 3 for each All Star Game, and 1 point for a Rookie of the Year award.

2 points for a Gold Glove at C, SS, or 2B, and 1 point for any other gold glove.

6 points if they were the regular SS or C on a WS team, 5 points for 2B or CF, 3 for 3B, 2 for LF or RF, and 1 for 1B. I don't have the OF distribution, so I give 3 points for OF.

5 points if they were the regular SS or C on a League Championship (but not WS) team, 3 points for 2B or CF, 1 for 3B. I don't have the OF distribution, so I give 1 points for OF.

2 points if they were the regular SS or C on a Division Championship team (but not WS or LCS), 1 points for 2B, CF, or 3B. I don't have the OF distribution, so I give 1 points for OF.

6 points for leading the league in BA, 4 for HR or RBI, 3 for runs scored, 2 for hits or SB, and 1 for doubles and triples.

50 points for 3,500 career hits, 40 for 3,000, 15 for 2,500, and 4 for 2,000.

30 points for 600 career home runs, 20 for 500, 10 for 400, and 3 for 300.

24 points for a lifetime BA over .330, 16 if over .315, and 8 if over .300.

For tough defensive positions, 60 for 1800 games as a catcher, 45 for 1,600 games, 30 for 1,400, and 15 for 1,200 games caught.

30 points for 2100 games at 2B or SS, or 15 for 1,800 games.

15 points for 2,000 games at 3B.

An additional 15 points in the player has more than 2,500 games played at 2B, SS, or 3B.

Award 15 points if the player's batting average is over .275 and they have 1,500 or more games as a 2B, SS or C.

Pitching Rules

15 points for each season of 30 or more wins, 10 for 25 wins, 8 for 23 wins, 6 for 20 wins, 4 for 18 wins, and 2 for 15 wins.

6 points for 300 strikeouts, 3 points for 250 SO, or 2 points for 200 or more strikeouts.

2 points for each season with 14 or more wins and a .700 winning percentage.

4 points for a sub-2.00 ERA, 1 point if under 3.00.

7 points for 40 or more saves, 4 points for 30 or more, and 1 point for 20 or more.

8 points for each MVP award, 5 for a Cy Young award, 3 for each All Star Game, and 1 point for a Rookie of the Year award.

1 point for a gold glove.

1 point for each no-hitter. This is not currently included.

2 points for leading the league in ERA, 1 for leading in games, wins, innings, W-L%, SO, SV or SHO. Half point for leading in CG.

35 points for 300 or more wins, 25 for 275, 20 for 250, 15 for 225, 10 for 200, 8 for 174 and 5 for 150 wins.

8 points for a career W-L% over .625, 5 points for over .600, 3 points for over .575, and 1 point for over .525, min. 190 decisions.

10 points for a career ERA under 3.00, min 190 decisions.

20 points for 300 career saves and 10 points for 200 career saves.

30 points for 1000 career games, 20 for 850 games and 10 for 700 games.

20 points for more than 4,000 strikeouts, and 10 for 3,000 SO.

2 points for each WS start, 1 point for each relief appearance, and 2 for a win.

1 point for each league playoff win.

Baseball Returns to Our Nation's Capitol by Nancy Golden

I think I lasted until nearly 4:00 at work that day, though my spotty long-term memory may be rewriting history in my favor. The platform of the Metro that I usually took home this afternoon seemed more crowded than usual, and when the doors slid open on the inbound train to DC I got my first taste of a sub-culture that had literally been born that day. What was normally a sparsely populated train of weary commuters returning home from their Northern Virginia jobs today was a buzzing sea of red hats and shirts that were all having the same conversation. I felt like I was riding the D train to Yankee Stadium during the postseason, and aside from those first few days of the NHL playoffs when we pretend that the Capitols might actually advance to Round 2, I had not experienced anything like it before in DC. It occurred to me how awful it would have felt at that moment had I simply been taking the train home instead of making my way to RFK Stadium.

For the past month, the Nationals home opener had been the hottest ticket in town. Seats had been held back when the rest of the individual games went on sale in hopes of retaining some bait to lure in additional season ticket purchases. By the time they were finally available to the general public, the supply had been depleted not only by season ticket holders, but lottery winners, promotional giveaways, Congresswomen’s husband’s drinking pals, and the usual crowd of the entitled that haunt the city. In fact, only single tickets were left for us mere baseball fans.

And yet I was never quite alone that night. In a packed Metro train, I managed to carve out a bit of space next to Stan, an older gentleman who claimed to be playing hooky from his post at the National Zoo. Stan held season tickets for the Washington Senators and had attended their last game in DC before that incarnation of the franchise moved to Texas in 1971. Tonight he would catch the very next home game, a moment for which he had waited 34 years. During our conversation, I never mentioned to Stan that I had waited merely a year and a half, basically the time since leaving my Camden Yards-friendly job in Maryland for one in Arlington, Virginia that separated me from weeknight Orioles games by an extra city’s worth of traffic. I didn’t feel as if my joy that the next homestand had finally arrived was any less than Stan’s at that point. We were both going to a baseball game. Tonight. In DC.

Amid the carnival atmosphere outside the stadium I met my friend Mike, whose 9-year old son Dana was playing in the makeshift amusement park of inflatable slides and slow-pitch target practice. Forced to pay Ebay prices for tickets, Mike, a native of the area could only bring one of his children to the game. Though I likened this to a Sophie’s Choice, Mike explained that 4-year old Alex might be too young to appreciate the event anyway. Knowing Mike was a big baseball fan, I asked Dana if his dad had taken him to a lot of Orioles games.

“No.”

Had he been to any baseball games?

“No.”

This is your first baseball game???

Dana was getting in from Day 1. He would be the first of his generation to be raised a Nationals fan.

After passing through the metal detector (a precaution for the President that would be dropped after tonight’s game), I watched the opening ceremonies from my infield upper reserve seat behind home plate. Brand new season ticket holders (aren’t they all?) Ken and Rick, who sat to my left, revealed to me how pleased they were with their seat selections, and we all agreed that RFK cleaned up surprisingly well for an infrequently used soccer venue. The packed house of diehard locals exploded as the festivities began and I—a transplant New Yorker steadfast Yankees fan—I could feel myself morphing into one of them with every cheer.

The pomp and pageantry, which so easily could have been overdone, was just right. On loan from the Kennedy Center, Renee Fleming sang the National Anthem as the obligatory patriotic mega-flag was unfurled in the outfield and the flyover tribute was quick and tasteful. Even President Bush kept his fanfare to a simple wave and trot as he threw out his first pitch, and I, riding the wave of good cheer, relegated my disgust for the war-mongering asshole to a charitable silent protest. And then the game began with what was by far the classiest moment of the evening. One by one, members of the Washington Senators were introduced and took their old positions on the diamond. When the full team was fielded and it was time for play to begin, the Nationals starters trotted out to their positions and shook the hand of the man he was to replace. Each Senator then took off his glove and presented it to his counterpart, as if finally, after three decades on call, he would no longer need it. I wondered how those transplanted Expos felt at that moment, without the luxury of my eight years to warm up to the city. It couldn’t possibly have meant us much to them as it did to the fans, and yet watching the Senators leave the field one final time to the roar of the crowd, it had to have instilled some sense of responsibility.

The Nats went on to the beat the Diamondbacks 5-3 that night behind the first of many solid outings from the moody-but-worth-it Livan Hernandez, and a 3-hit, 4-RBI night from Vinny Castilla. And we got our first peek at some of RFK’s peculiarities, like the way the entire third base field level section bounces when enough people jump up and down, or how somebody someday must have thought it was a good idea to paint the 400-level seats mauve. Other quirks would wait for future games to show themselves, like the way the deep outfield turned out to be not quite as deep as it was labeled, or that odd eagle-like mascot that looks like it’s suffering from bloating and edema. (I know, I know, Screech was designed to appeal to kids, not anal wildlife biologists.)

And we’ve had plenty of opportunity to experience them all. From blind dates that I might not otherwise have agreed to, to premier seats with out of town visitors (including Zisk editor Steve Reynolds, down for the very first series against the Mets), to last minute excursions after a taxing day at work, baseball in DC has become the norm. The average game draws over 30,000 people, compared to those 16 or 17 fans that used to show up in Montreal. And when John Patterson claims to be pitching better due to DC’s amazing fan support, I choose to believe him, even if he is clearly just sucking up. Men, women, and kids sport Nationals caps everywhere you turn, and newspapers run stories on whether your choice of a red “W” cap or blue “DC” cap is some kind of a political statement. (I say let’s reclaim the “W.” And the color red while we’re at it.) And like New York, Cincinnati, Milwaukee, and yes, even the evil Boston, we talk baseball again. We weather the highs and lows together every morning at work, and suffer the occasional indignities, like when Joe, the resident Braves fan, brought his tiny little broom to my office after Washington was swept by Atlanta. Mike’s sons even request play-by-play at night now in lieu of bedtime stories. And I’m finally accepting that despite being spoiled by the Nats unexpected success in the first half, being “only” in Wildcard contention (reminder to self—these were the Expos) is pretty damn sweet.

Some of my New York friends have branded me a traitor for this show of enthusiasm for my new hometown team, even though the Yankees don’t play the Nationals this year, and I argue that I can safely root for both clubs. Though many just ask where my loyalties would lie if forced to make a choice, as if there’s even a question. Let me go on the record to say that in the unlikely event that the Nats meet the Yanks in a World Series, I, like most transplants and transients in this city, will revert back to my roots. But in the meantime, I will continue to enjoy the new experience of rooting for a bunch of guys—ballplayers—a team—who are not defined by their salaries, steroid use, haircuts, or egomaniacal owner (the Nats don’t even have an owner), but by last night’s play at second or the ability to make a key 2-out hit in the 8th. I often think back a few years to a screening I attended of The Life and Times of Hank Greenberg in which filmmaker Aviva Kempner stood before the audience and appealed to us and to the league to bring baseball back to DC. We don’t need baseball in DC, I thought on the first of many occasions, we have the Orioles. I know now that I was wrong. We do need baseball. I’ve changed. I believe.

Dr. Nancy Golden has been a Yankees fan all her life, yet she and Zisk co-editor Steve Reynolds still remain friends. (She has a doctorate, so we can call her ‘Doc.’)

Hey Nineteen by Art Webster

But what of the fellows who fell one game short of infamy? The guys who can never use “I’m a 20-game winner” as a pickup line on a fledgling baseball Annie? The doorstep guys ostracized because of a lucky bounce or lack of run support?

Let’s call our 19-game winners/20-game-nonwinners The Blasskickers, after patron saint Steve Blass. Blass, of course, won 19 games in 1972 and, having fallen one victory short, apparently snapped. After having averaged slightly under three walks per nine innings throughout his career, Blass suddenly couldn’t throw strikes in 1973. In 87 innings, he walked 84 and hit 12 bewildered batsmen.

Steve’s not the only Blasskicker with an interesting back story.

There’s his teammate Dock Ellis, who, before winning 19 in 1971, dropped a hit of acid before a 1970 game. He naturally pitched a no-hitter. If you’re reading this, you almost certainly know the story (see: Barbara Manning songs; LSD, users of; Baseball Babylon, etc.). If anyone has television or film footage of this remarkable achievement, please send it to Mike or Steve, at the address listed in the front of this magazine. They’ll reward you handsomely. (We have no cash to offer—SR.)

Whereas the Big Red Machine was never known for its starting pitching, Jack Billingham won 19 games for the team in both 1973 and 1974. In a rarity for the early 1970s Reds, the team didn’t win pennants either year. I blame Billingham. Loser.

Also in 1974 came the first quality, relatively speaking, season by Jim Bibby. We could call him a Blasskicker Extraordinaire, but it’d make more sense to call him Mr. 19. In ‘74, he won 19. He also won 19 for the 1980 Pittsburgh Pirates, making him one of two cats on this list to win 19 for two different teams. The reason I really like Bibby, though, is that he also lost 19 for Texas in 1974. Man, talk about cutting it close. He could have been 18-20. Or 20-18. You’ll never be Mr. 19 by going 20-18.

He’s also kind of a 19-game winner in overall life. His brother is Henry Bibby, a UCLA Bruin great on those Bill Walton teams in the early 1970s. His nephew is Mike Bibby, a damn good NBA player in his own right. Mike Bibby could probably buy and sell Mr. 19 several times over.

The coolest 19-game winner, nudging Dock Ellis, was Detroit’s Mark Fidrych, who would have won 20 except that he wasn’t called up to the team until the season was a few weeks old. Poor guy. Good pitcher. Good fastball and curve. Great control, except in the crotch area. The rumor about him was that a jealous husband twisted his arm.

A future Tiger, Frank Tanana, also won 19 games in 1976 for the Angels (he played a key role when the Tigers stole the 1987 division title from the Blue Jays; that’s a completely different story). The thing about Tanana was that he threw, like, almost as fast as Nolan Ryan and was a bit arrogant as well. Then he found God and, well, I don’t know if it was the natural aging process or an arm injury or the whole God thing or what but all of a sudden, he became a really lame-looking finesse pitcher. A finesse pitcher who lasted forever, but, nonetheless, a finesse pitcher really into God, which made him, let’s face it, not cool. He was no Fidrych, anyway.

Former Cub Burt Hooton came up one short in 1978, when hurling for the Dodgers. Hooton was an early knuckle-curve auteur, pitching a no-hitter in his fourth major league start, in 1972. I think his nickname was “Happy,” and supposedly, it was one of those ironic nicknames often given to a sourpuss guy. Probably wasn’t too happy that he never won 20.

Steve Rogers of the Expos was always considered one of the game’s best pitchers during the latter 1970s. Yet, like his really good bridesmaid team, he never quite finished the job, falling short of the 20-game mark in 1982. Can’t believe that’s the most he ever won; I’m gonna check it. Yup, he won 17 twice, and had a career ERA of 3.17. If he were pitching today, he’d be on the Yankees. And probably winning 20.

Then there’s crusty John Denny, who won the Cy Young Award with his 19-win season in 1983. Can’t remember where I read this, but wasn’t Denny supposed to be a jerk? Or was that John Smiley? I always get those guys mixed up. (If John Smiley’s a prick, would they, as they did with Happy Hooton, call him Smiley Smiley? Do you think John Smiley is a Brian Wilson fan?)

Dan Petry won 19 for the Tigers in 1983, then won 18 for them the next year as the team out-and-out dominated baseball. Mark Langston won 19 for the 1987 Mariners and 19 for the 1991 Angels. Storm Davis and Mike Moore both won 19 for the 1989 A’s. Man, baseball was boring back then. Hmmm. Who won the 1989 Cy Youngs? Bret Saberhagen, for Kansas City. Boring. Mark Davis for San Diego. Are you kidding me?

Mike Mussina won 19 games for both the 1995 and 1996 Orioles. I remember this well. In the game after Roberto Alomar spit on John Hirschbeck (the Orioles clinched the wild card that game), Mussina gave up a home run to someone to tie the game in the ninth. Maybe I don’t remember it. Maybe he lost his bid in the same Roberto Alomar game. Bet’cha Mussina remembers it. Dude’s got his economics degree, in just three years, from Stanford. Man, with his stuff, he should have won 20 four different times and pitched two no-hitters. And with his brain, he should be a special assistant to Alan Greenspan.

During the late 1990s, a bunch of yawners won 19. Shawn Estes did it in 1997 for the Giants. Aaron Sele did it in 1998 for the Rangers. Shane Reynolds did it in 1998 for the Astros. Kevin Tapani did it in 1998 for the Cubs. Tapani won his 19 despite his 4.85 ERA. God, what’s this game become? Oh yeah, that’s right, 1998, the ‘Roid Year. Never mind.